Orrin C. Evans (1902-1971) was considered the dean of Black journalists.

At age 17, he worked for a small sports publication before becoming a reporter at the Philadelphia Tribune and later returning as its managing editor, according to his obituary. He was a managing editor for the Philadelphia edition of the Baltimore Afro-American. He also was editor of the Philadelphia Independent, a Black newspaper started in 1931, and owned by Forrest White Woodard and his wife, Kathryn Fambro Woodard.

Evans was the first Black general assignment reporter at a major metropolitan newspaper in the country. He worked for the white Philadelphia Record in the 1930s and 1940s. He left the Record after it was sold in 1947. He also worked for the Chester (PA) Times as a reporter and desk man in the 1950s.

He was hired by the Philadelphia Bulletin in 1962 and stayed there for nine years. He covered the civil rights movement as well as city government. At an NAACP convention in 1971, he was cited for his work and was given a surprise party. It was there where he was described as the dean of Black newspaper journalists. According to his obituary, the convention was covered by 18 Black journalists from across the country. He was director of the Philadelphia Press Association.

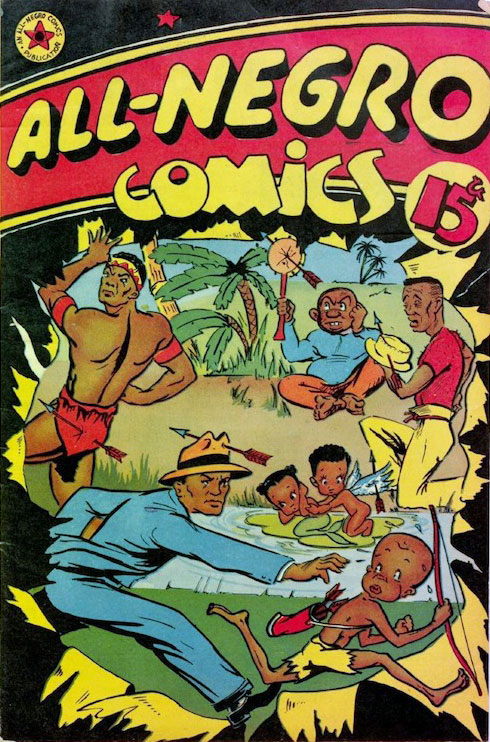

In 1947, Evans and four other Black men published the country’s first Black comic book, “All Negro Comics.” Only one issue was produced, “All Negro Comics #1.” He was thwarted when companies would not sell him newsprint for a second issue.

Mal (Malvyn) Johnson was a pioneer Black TV reporter who got her start at WKBS (Channel 48) in Philadelphia (the station is no longer in operation) in 1966. A schoolteacher, she was bored with teaching and decided to apply for a community relations and public affairs position at the station. When she arrived for an interview, the white male personnel officer would not hire her because she was Black. He had only spoken to her on the phone and assumed she was white. Soon after, the owner of the station called her and gave her the job. Johnson started out writing about club news, but went on to report on community and national groups. She eventually hosted three programs on WKBS: “Coffee Break,” “Dialing for Dollars” and “Let’s Talk About It.” In 1969, she was hired by Cox Broadcasting Corp. (based in Atlanta) and in 1970, became its Washington, DC, national news correspondent. She was the third Black woman admitted to the White House press corps. (The other women were Alice Dunnigan and Ethel Payne. The first Black journalist to cover the White House was Harry S. McAlpin as a correspondent for the Atlanta Daily World in 1941. He was banned from being a member of the white press corps. His articles were disseminated to other Black newspapers under the auspices of the National Newspaper Publishers Association.)

In 1972, Johnson was one of three women who accompanied President Richard Nixon to Russia. Johnson was a member of the American Women in Radio and Television and served as chairwoman of its foundation. She also served as the community and public affairs director at Cox.

Fletcher J. Clarke started as a clerk/copy boy at the Philadelphia Bulletin in 1961 as a suburban and police reporter. He was a panelist on “Black Perspective on the News” in 1971. Clarke stayed with the paper until 1972. In 1970, he participated in the Summer Program for Minority Journalists at Columbia University and became the program’s deputy director in 1972. Clarke joined Gannett newspapers in 1973 as a copy editor for the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, followed by a stint with the Gannett News Service from 1974 to 1977. He was named managing editor of the Niagara Gazette in Niagara Falls, NY, in 1977. He also served as associate editor of the Forum, the editorial page at the Courier Journal in Louisville, KY.

John H. Terrell was a cartoonist. He worked at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard and illustrated its Shipyard Beacon. He also worked for the Philadelphia Tribune. He was a contributing cartoonist to Orrin C. Evans’ “All Negro Comic #1,” illustrating the detective Ace Harlem and the characters in “Lil’ Eggie.”

Matt Robinson Jr. was a writer, producer and on-air talent at WCAU-TV, starting at the station in 1963. He hosted and produced a weekly TV show called “Opportunity in Philadelphia,” a job-listing program that catered to Black job-seekers. His father, Matt Sr., was a postal worker who wrote for the Philadelphia Independent. Matt Jr. created the character Gordon on “Sesame Street” and wrote for the “Cosby Show.”

John Brantley Wilder was a journalist, painter and civil rights activist. He was a painter who worked as a journalist so he could afford to create art. He was a reporter, education editor and columnist for the Philadelphia Tribune from the 1960s to 1970s. In the late 1940s, he conducted a one-man campaign to spur Hollywood to hire Black actors for non-subservient roles.

In a 1989 report, the Inquirer compiled a list of minorities and women who were hired from the 1950s to 1970s. (The info below has been supplemented by newspaper research.) The Black journalists, including Acel Moore, who joined in 1962 as a clerk/copy boy:

Robert “Bob” Thomas was the first Black reporter at the Inquirer, hired in 1953. He resigned in 1964 to join the U.S. Information Agency. A graduate of Temple University, he was initially hired as a copy boy. Thomas was known for having been chosen for the NBC-TV feature “Big Story” in 1957. The “Big Story” was a live TV program based on a radio series that dramatized major newspaper stories and their reporters across the country. The show featured a narrator and actor who portrayed the reporter, who appeared at the beginning and end of the show. Thomas beat out hundreds of editors and reporters at Black newspapers for his spot on TV, according to a news story. For his big story, he infiltrated a teenage gang. Actor Terry Carter portrayed Thomas, who appeared at the end to receive a $500 prize.

William “Bill” Thompson was hired in 1960 as a clerk/copy boy after graduating from Temple University with a journalism degree. He rose to become the newspaper’s second Black reporter. He eventually filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, citing racial discrimination by the Inquirer. The newspaper settled, Thomas received a cash payment, and the Inquirer agreed to hire three Black reporters. Thompson retired in 1994 and died two months later of a heart attack.

Charles H. Thomas was hired in 1963. He was a general assignment reporter with the Philadelphia Tribune from 1959-1960, worked in the Circulation Department of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and at the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission. He also worked for the Pittsburgh Courier and as a police officer. At the Inquirer, he was a reporter covering the federal courthouse. In 1969, he died in the crash of a plane that he was piloting).

Dennis Kirkland was hired as a clerk/copy boy in 1962, the same time as Moore. He had also worked for the Philadelphia Bulletin. After 14 years, Kirkland left journalism to join the Philadelphia Housing Authority. “The porters and the elevator operators used to give us a hard time, because we were young cats,” Kirkland told Tribune reporter Paul Bennett in 2001, referring to himself and Moore. “But when we got promoted (to reporters) all of a sudden we were their heroes, their role models.”

Art Peters was hired in 1971 as the Inquirer’s first Black columnist. He was the first Black copy boy at the Washington Times Herald and later became a reporter. For seven years he was a freelance writer in New York, penning articles for such publications as Ebony, Look and TV Guide. He came to Philadelphia in the 1950s and worked as a reporter for the Philadelphia Tribune. He also did news commentary for WDAS radio. He became the Tribune’s city editor, resigned after three years and eventually got a law degree from Villanova University. He passed the bar in 1971 and at the same time was offered a job as a columnist at the Inquirer. He died in 1973. Acel Moore was instrumental in organizing a copyediting training program in his name at the Inquirer.

The Philadelphia Tribune

The Tribune has a long history, serving as a both a temporary stop and destination for many notable Black journalists. It is the nation’s oldest Black newspaper, founded in 1884 by Christopher James Perry. He was an editor of the “colored” section of the white-owned newspaper “The Mercury,” where he wrote a column “Items on the Wing.”

Among the Tribune’s writers were William C. Bolivar, a columnist and Black history collector; Dorothy Anderson, Jack Saunders and Billy Rowe, columnists; Ruth Roland, reporter; Malcolm Poindexter, controller, reporter and sports editor (who was the great-great nephew of Thomas Morris Chester of Harrisburg, PA, according to the Tribune. At age 30, Chester covered the Civil War for the white Philadelphia Daily Press and wrote his story about the capitulation of the Confederate capital in Richmond while sitting in a chair owned by Confederate President Jefferson Davis), and Eustace Gay, columnist, editor-in-chief and managing editor.

Others were Evelyn Reynolds, social columnist who wrote under the pen name “Eve Lynn”; W. Randolph Dixon, sports editor; Joseph Rainey, sports columnist and writer; Mamie Robinson, “Women in Politics” columnist; Ora Brinkley, food writer and lifestyle writer, a member of the ABJ in its early years; Louis Potter, civil rights editor (also was a news editor and producer at WCAU-TV in charge of its nightly newscast); Ralph H. Jones, executive editor; photographer Jack Franklin. t