The origin of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists dates to 1973 when Black journalists began gathering and commiserating about the conditions at the white newspapers, TV and radio stations where they worked.

There were too few of them. They were not given the best assignments and not equally promoted. They were not allowed enough face time on the air. They were not treated fairly. The atmosphere in the newsrooms was toxic.

“We started talking about our common concerns – the low number of Blacks in the media from print to broadcast,” said Sam Pressley, a reporter at the Evening Bulletin at the time. “We also were concerned about the way Blacks and the Black community in general were covered, often in a negative way. If you read the Inquirer and the Daily News – especially the Daily News – and to a certain extent the Philadelphia Tribune, it was always about crime.”

Acel Moore, then a reporter at the Philadelphia Inquirer, said the meetings were the start of what became a long-term strategy.

“It was an attempt from the beginning to increase our numbers, to be in a position to tell our own stories, to be a pressure point inside the industry,” he said in 2003 on what was then considered the 30th anniversary of PABJ.

Soon, they were meeting for a purpose. They weren’t sure how many of them were working in the Philadelphia region, according to Pressley. So they began their own calculations: noting new faces that turned up at assignments they were covering and noticing any who were on-air. They identified 76 working journalists.

“Black Perspective on the News” and other programs

Meanwhile, Moore and Reggie Bryant in 1973 started co-hosting and co-producing “Black Perspective on the News,” a local news-analysis program on WHYY-TV that had been canceled by budget cuts in 1971. A year later, in August 1974, it became the first WHYY-TV weekly series to broadcast nationally on PBS. Several ABJ journalists also conducted some of the “Meet the Press”-like interviews.

“The fact that there are two societies, two lifestyles, … Black and white, and the unique position of the Black journalist as participant in both, is probably the most exciting concept behind the program,” Moore said in a 1973 article in the Michigan Chronicle (Detroit).

“This program affords the journalists on the panel the opportunity to ask questions from their own unique positions, from ‘two sides’ as it were, and this broad basis is what makes the program important to Black and white audiences.”

“Black Perspective” was originally created and produced in 1968 by Lionel J. Monagas, the first Black professional at WHYY. Monagas also hosted “New Mood, New Breed” on WHYY in the late 1960s.

In the early 1970s, according to a May 1971 mention in Jet magazine, another producer of “Black Perspective” was Jimmy McDonald, one of the original 1961 Freedom Riders. It had aired in 32 cities in 16 states via the Eastern Education Network.

“Black Perspective” was not the only locally produced news and analysis show aimed at a Black audience. With a push from its Black staffers, KYW-TV in 1971 created “Black Edition” with hosts Malcolm Poindexter and Jesse Brown, along with Trudy Haynes. Moore was among the contributing reporters, as well as Joe Donovan, Dave Valentine, Teresa Brown, Claude Lewis, Pamela Haynes and Clay Dillon. Clarence Farmer Jr. was the producer.

Impetus to form a journalists’ group

At the Evening Bulletin, a group of Black journalists – including Pressley, Don Camp, Elmer Smith and Laura Murray – were meeting with top editors to push for the hiring of more Blacks in their newsroom, according to Camp, then a photographer. Eventually, a few were hired, he said.

Chuck Stone, Claude Lewis and Moore recalled meeting to discuss the idea of forming a Black journalists’ organization. According to Moore, they sent out letters on their respective newspapers’ letterheads to up to 50 journalists in the area during the spring of 1973 inviting them to meet. (This may have been the spring of 1974, but we have no documentation.) The three, along with Bryant, were the “main antagonists” of the movement, according to Smith.

“I would give them credit for (sending the letters),” said Pressley. “We were negotiating with the editors at the Bulletin to hire more of us. Acel was trying to do the same thing there at the Inquirer. When Chuck came to town (early 1973), he was high profile as a columnist. It was very apparent to us that we needed high-profile Black folks to be able to attract other Black folks. In other words, Sam Pressley didn’t have a name per se or Francine Cheeks didn’t have a name per se. Pamela Haynes didn’t have a name per se.”

Bryant described himself in 2003 as the “agent provocateur” and never ran for office in ABJ. “I resisted holding office because it gets you into the protocol, and again we found that Black folks were operating with Roberts’ Rules of Order, many of whom had no idea about Roberts and the origin of parliamentary proceedings,” he said. “It just seemed to me to be contradictory, so I never stood for office.” He would eventually scold the organization because he thought it had lost its bite.

Publicizing the formation of ABJ

The journalists announced the formation of the Association of Black Journalists in a press release on Oct. 31, 1974. Several media outlets publicized it. According to the Philadelphia Daily News, a spokesman said the organization was formed in June 1974 and had 50 members.

Stone noted in a 1976 column that the group was formed in the summer of 1974.

Lewis mentioned the founding of ABJ in a 1987 column: “NABJ had its beginnings in Philadelphia in 1974. The first meeting was attended by three journalists. Present were Acel Moore of the Philadelphia Inquirer, Chuck Stone of Philadelphia Daily News and I. I was associate editor of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and the first black columnist in the region. … We began the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists. In less than a year, a bevy of blacks from newspapers and broadcast

media from around the country gathered in Washington to create the National Association of Black Journalists.”

So far, no sign-in sheet from the organizing meeting of the ABJ has turned up. Tyree Johnson recalled that the meeting occurred in a bookstore on the second floor of Progress Plaza in North Philadelphia, one of two places where they held meetings.

The ABJ was the country’s first incorporated “Association of Black Journalists.” Members knew of no other organization with that name, several of them said. “It was very simple to call ourselves ‘the Association of Black Journalists’ because there was nothing in New York, there was nothing in DC, there was nothing in Detroit or Chicago,” said Pressley. “We were it.”

It would be a year later, on Dec. 12, 1975, before a national organization would be formed in Washington, DC.

ABJ was not the first Black media organization in Philadelphia. In 1932, a group of Black male journalists working for three Black newspapers in the city formed the Philadelphia Reporters’ Association. Joseph V. Baker of The Philadelphia Tribune and Julian St. George White of The Philadelphia Independent were the organizers.

The group held its organizational meeting on Oct. 21, 1932, adopted a constitution and governing laws, and elected officers. It consisted of writers and advertising men from The Tribune, The Independent and the Afro-American (Baltimore). The association was open to all men whose primary income came from working at newspapers. Women were barred from membership.

The officers were: White, president; Joseph H. Rainey Jr. (Tribune), vice president; Baker, secretary, and Eustace Gay (Tribune), treasurer. Other charter members were: W. Randolph Dixon, Kenton Jackson, Prince L. Edwoods, Harold Harbison and Samuel A. Haynes (Tribune); E.W. Baker (Afro-American), and Alton “Chippy” Berry, Orrin C. Evans and W. Rollo Wilson (Independent).

The association held banquets and forums on issues of the day.

In 1971, Black Communicators Inc., consisting of journalists and other media professionals, was formed to force TV stations to hire more Blacks by challenging their Federal Communications Commission (FCC) licenses, according to Miller Parker, president of the organization in 1971. WPVI-TV was the first to be challenged, he said in a 2017 interview.

Nationally, several organizations of Black journalists had formed in the late 1960s, but none with the name “Association of Black Journalists.” All had the same aims and reasons for organizing.

In 1967, Black Perspective was formed in New York by 40 journalists on the East Coast. Thomas A. Johnson, a reporter at the New York Times, was one of the co-founders. In 1972, Johnson joined 75 Black journalists in Washington to discuss a national organization.

In November 1967, a group of Black journalists, media professionals and others called Black Perspective, which had recently formed, held its fourth monthly meeting in Washington, DC, hosted by Robert Maynard of the Washington Post, Lawrence A. Still of the U.S. Department of Labor and Ernest Holsendolph of the Washington Star. Among its members were journalists, freelancers, photographers, a member of SNCC, the Urban League and the U.S. Labor Department. (It’s not clear if this was the New York group or was related in some way to it.)

An article in the Chicago Daily Defender noted that Black Perspective was dominated by journalists from New York and Philadelphia. In newspaper stories, it was often described as an organization of New York journalists but also as a national organization with chapters in Washington, New York and Philadelphia whose members were either all journalists, or journalists and media professionals.

In Los Angeles in 1968, a Black Perspective organization tied to the New York group was headed by LA Times reporter Ray Rogers. A Pasadena, CA, newspaper reported that the organization was formed the year before, after the Detroit riots.

In 1968, the United Black Journalists was formed in Chicago, with Francis Ward of the Chicago Sun Times, Carole Simpson of WMAQ-RV (NBC) and Barbara Reynolds as leading figures. L. F. Palmer was also involved. The Chicago group was around until at least 1979. In New York, Black Perspective was still meeting at least until 1976.

Each of the Black Perspective groups supported New York Times reporter Earl Caldwell in 1970 in his efforts to reject a federal subpoena regarding his reporting on the Black Panther Party.

A daring undertaking

As for ABJ, “we considered it bold back then,” Lewis said. “An association of BLACK journalists? Wow.”

They had reason to be afraid. They could easily have been fired from jobs that had been so hard to get. Some Blacks shied away from the organization for that reason. “Racism was more pervasive, very much out in the open then,” said Moore, noting that other Black organizations perceived ABJ as “militant.”

“What must never be forgotten – and acknowledged today – is that PABJ was ridiculed from some of our racist colleagues in the media,” said Stone. Added George Strait, then a reporter at WPVI-TV: “You have to understand, this was a scary thing to do. First of all, we didn’t know how our white bosses would react to this. We’re all – except for Chuck, who was pretty stable (at the Daily News) – relatively young in our careers. So there was a lot of concern. You can call it fear, if we did this that we could be retaliated against. “

In 2003, J. Whyatt “Jerry” Mondesire recalled that white editors at the Inquirer set up a betting pool to see how long Moore would last. Moore often told stories of being called “Boy” until he had a straight talk with some editors. He started at the paper in 1962 as a clerk/copy boy; only two other Black men had been hired in the newsroom before him. Walter Annenberg, owner of the paper, “did not want Black people working here (at the Inquirer as journalists),” Mondesire said.

Camp noted that the Civil Rights movement drove white media companies to hire Blacks. “Industries were searching for ‘tokens,'” he said. “Many of us filled the roles of tokens, but we had to be very good to get and remain in those positions.”

Black journalists weren’t openly embraced by everyone in their own community. Chuck Stone was attacked by the executive director of the local branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at a School Board meeting in June 1975. The ABJ called on the national office to dismiss him.

At a 1975 press conference, ABJ members decried recent attacks on Black journalists: Lewis was the subject of bomb threats from a caller to his home and racist notes from inside the Bulletin newsroom, and Tyree Johnson drew the wrath of the Black Mafia, which allegedly had put out a murder contract on him. Johnson had written stories about the group for the Daily News. Strait was harassed by the local teachers union for reporting that Black schools had remained open during the teachers’ strike in the early 1970s.

ABJ’s officers and objectives

In the November 1974 press release, the ABJ announced these officers and board members:

- Chuck Stone (Philadelphia Daily News), president

- Pam Haynes (Philadelphia Tribune), vice president

- Sam Pressley (Evening Bulletin), secretary

- George Strait (WPVI-TV), treasurer

- James C. Johnson (Evening Bulletin), assistant treasurer

- Claude Lewis (Evening Bulletin), chairman of the Executive Board

The Executive Board:

- Francine Cheeks (WCAU-TV)

- Joe Donovan (KYW radio)

- Artis Hall (WCAU-TV)

- Carole Norris (WHYY-TV)

Others at the meeting or had attended gatherings, based on journalists’ recollections, were:

- Reginald Bryant

- Lamont Steptoe

- Harold Yates

- Jan Gorham

- Malcolm Poindexter

- Alphonso D. Brown Jr.

- Don Camp

- Elmer Smith

- Tyree Johnson

- Bob Perkins

- Paul Bennett

- Greg Morrison

- J. Whyatt “Jerry” Mondesire

- Earl E. Davis Jr.

- Eddie Stinson

- Kendall Harris

- Laura Murray

- Mal Johnson

The press release included a mission statement with 10 objectives:

- encourage more Blacks to enter the profession

- serve as a clearinghouse for job opportunities in the news media

- recruit more Black high school students for journalism schools

- help young Blacks with scholarship grants and professional assistance

- expand the teaching opportunities for Blacks in journalism schools

- provide support for racial discriminatory complaints filed with official agencies

- sensitize the white media to a more balanced coverage of Black communities

- maintain liaison with other Black journalist groups throughout the country

- recognize outstanding journalistic talent within its own ranks

- develop closer ties with other Black professional organizations

Meeting with Temple University

In ABJ’s first official business, Moore, head of its Equal Opportunity Committee, and the Executive Board had “recently” (Stone noted in a later column that it was September 1974) met with officials of the Temple University School of Communications to discuss the dearth of Black students and faculty, according to the press release. Temple had accepted ABJ’s offer to help recruit students and appoint more Black journalists as instructors, according to newspaper articles based on the press release.

In an April 1977 column, Stone wrote that the group chose Temple because it was a public university, was located in the middle of a Black community and 20 percent of its student population were Black. He noted that Temple did not have a single Black faculty member in September 1974 when the ABJ held talks. A former Temple journalism department chair pushed back against Stone’s allegations.

The ABJ also went after Temple because it needed to position itself as a serious professional organization that acted on the issues affecting Black journalists, Roger Witherspoon said in 2003.

Temple’s communications school had reported in 1970 that surveys of newspapers across the country showed that the number of Black reporters, news executives, photographers and desk editors was miniscule, just under 2 percent. The number was no different for Black students at white colleges and universities.

In 1977, ABJ and Temple participated jointly in journalism-training programs for local high school students.

Fundamentals of the new organization

The newly formed ABJ met every third Wednesday of the month at the Institute for Black Ministries, at Broad Street and Girard Avenue in North Philadelphia, according to the Daily News and Inquirer articles from the press release. Journalists also met at Progress Plaza in North Philadelphia.

A committee that included Morrison, Norris, Bennett and Stinson drew up the constitution/bylaws. Earl E. Davis Jr. of the Philadelphia Inquirer created the ABJ logo, which emphasized the members’ African roots, according to members. Barbara Johnson, wife of Tyree Johnson, designed and hand-stitched a banner that was hung at the first banquet in 1976, Tyree Johnson said.

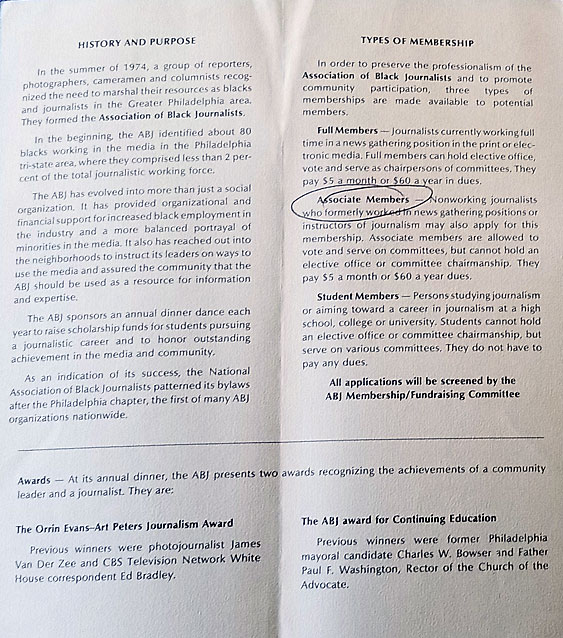

The journalists were very specific about who could be members, according to undated bylaws in the papers of Acel Moore at the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University. Membership was open only to working journalists, reporters, editors and photographers. Full membership required two or more years’ experience and associate membership, fewer than two years. Students were required to be studying journalism at a college or university.

Officers served one year with no more than two consecutive terms. Dues for full members: $25 initiation fee and $5 a month; associate, no initiation fee unless the person became a full member, $5 month; students, no fee or dues.

“Photographers kind of had a lesser standing,” said Camp. “We weren’t in a sense real news people. We provided art, which still annoys me because if you don’t know how to tell a story with pictures, then you’re not a photographer. So, we don’t write stories, we photograph stories and you gotta have a skill to do that.”

Johnson, one of the youngest members at the time, joined the gatherings after an invite from Stone. In considering a name for the group, he recalled the journalists saying, “’What are we going to name it,’ and they said, Black professional journalists. Chuck said journalists are professional, so we don’t have to say professional. I remember that conversation. Chuck was really the leader … there was a little, very slight friction about who’s going to lead it because it had another great Black (columnist) Claude Lewis. I can’t remember anything he said, but he was instrumental in forming the group. (Lewis was associate editor of the Evening Bulletin.)

“I remember Chuck saying drop the professional and say Association of Black Journalists. Chuck was really the driving force.” Among the other leaders were Lewis, Moore and Bryant, he said.

Incorporating ABJ

Mondesire filed incorporation papers for the Association of Black Journalists of Philadelphia on Dec. 15, 1975, three days after the founding of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ). The incorporation was approved by the state in January 1976. Moore said in a 2013 PABJPrism video interview conducted by member Manuel McDonnell-Smith that “Philadelphia” was included to distinguish it from NABJ. Morrison said the incorporation positioned the ABJ as its own entity rather than a subsidiary of NABJ.

The incorporation was amended in a filing in 1979 by then-president Tyree Johnson to expand the objectives of the organization, and to comply with state and federal rules.

“We really earned respect, and showed our strength to the media owners and the general public,” said Cheeks in a 2003 interview. “We recruited our members early on, but later people were coming to us asking to join and be a part.” She was vice president in 1976.

A dearth of female journalists

Cheeks lamented the scarcity of Black female reporters at local white TV stations in the early 1970s. Reporters on the streets – and editors behind the scene – were largely male and white with a sprinkling of Black males. Reporters were identified in stories as “newsmen.”

Other Black women at white publications included Haynes and Huggins. They “struggled and were alone an awful lot,” Cheeks said in 2003. Haynes was a reporter at KYW-TV. She became the first Black TV reporter in Philadelphia when she was hired by the station in 1965. Huggins was a reporter at WCAU-TV. She started at the station in 1966. In 1974, she hosted the program “Morningside With Edie Huggins.”

Also among the first Black women in TV in Philadelphia was Mal Johnson, who was hired in 1966 by WKBS-TV. She hosted three programs at WKBS until 1969 when she was scooped up by Cox Broadcasting Corp. She became a national news correspondent for Cox in Washington, DC, in 1970. Johnson was the first Black woman in the White House Press Corps and accompanied President Richard Nixon to Russia in 1972. She was working in Washington when ABJ was formed.

Haynes noted in 1969 that her problem was a lack of acceptance. She made her remarks in a column by a writer who described her as “someone who looked Venus of Milo (with arms) than an ace newspaperwoman.”

“My difficulty comes not in the city room, but on the streets, covering assignments,” said Haynes, then a reporter at the Philadelphia Tribune. “Especially with cameramen. At times, they want to move all over me as if I were part of the local scenery. It’s difficult for these men to accept a woman, especially a Black one, to be covering first rate stories. They expect us to cover only society news and social events.”

ABJ’s banquet programs from 1977 and 1978 list more than a dozen female members – 14 in 1977 and 13 in 1978, along with two as associate members.

Acrimony – and togetherness – among some members

The organization’s founding was not necessarily an easy task among its members, according to several journalists. The meetings were sometimes raucous because there were so many strong personalities in the room.

“Journalists had egos,” said Johnson, ABJ’s third president. “Some of the meetings got so bad that two of the members went out to a fistfight, really, and one them came back bloody. That’s how bad it was. … It was really something.” The combatants were Pressley and Bryant, according to Pressley.

“We were fractured as a group,” said Lewis. “I’m surprised (ABJ) survived. It got better over the years.”

On Friday nights and weekends, the journalists put aside their differences and met up to have a good time. They got together after work to party, many times at the Fox Trap disco club in Old City Philadelphia but also at members’ houses. They had parties just for fun, mingling with politicians and local leaders, and dances to raise money for scholarships, Pressley said.

“Because we were journalists, a lot of bigwig politicians, union leaders would deliberately come to our events just to socialize with us,” Pressley said.” I remember to this day there was this big-time union leader, I was dancing and he asked to hold my coat because I was dancing out of my coat. … We were very professional, but we took the time to party, and in partying we realized we ushered in another area of networking.”

Banquets as key fundraisers

ABJ planned annual banquets with national speakers. There seemed to have been no fundraising banquet in 1975.

Mark Hyman of Mark Hyman and Associates and account executive Violet “Vi” Johnson helped organize the first two banquets. “It was so fantastic,” Violet Johnson recalled of the first banquet in a 2003 interview. “They were so happy. They made more money than they expected.”

Corporations bought tables but didn’t show up, she said. The group made about $2,000, she recalled, and the banquet drew about 1,000 people.

PABJ was a client of Hyman’s company and Moore was a friend. “He knew Acel,” she said. “They (the Inquirer) were right across the street from our office.”

First banquet, 1976

That first annual awards and dinner-dance was held on Feb. 28, 1976. Federal Communications Commissioner Benjamin C. Hooks was the speaker. Sen. Hubert H. Humphrey, in town for a labor dinner, dropped in and gave a brief speech.

Famed New York photographer James Van Der Zee was awarded the Orrin Evans/Art Peters Journalism Award. Charles W. Bowser, an attorney and a former executive director of the Philadelphia Urban Coalition, received the ABJ Award for Continuing Excellence.

Evans was the first Black general assignment reporter at a major metropolitan newspaper in the country. He had worked for the white-owned Philadelphia Record in the 1930s and 1940s. Peters was a columnist at the Inquirer and a leading Black journalist in Philadelphia in the early 1970s. Both had also worked at the Philadelphia Tribune.

Moore remembered 1,000 people attending the event at the Sheraton Hotel, 17th Street and JFK Boulevard. The dinner was a fundraiser for student scholarships, according to Stone. It was the first year that scholarship money was awarded, funded by ticket sales. Tickets were $25 and $40 per couple. (“Yes, I know it is expensive,” Chuck wrote in a column at the time, “but so is the cost of attending journalism school and Black kids aren’t wealthy.”)

That first banquet sparked a tiff between the ABJ and the Philadelphia Tribune after Tribune columnist and ABJ member Harry Amana wrote that the newspaper had been snubbed during the event. Amana accused the organization of failing to mention the Tribune when it acknowledged the city’s three daily newspapers (presumably Inquirer, Bulletin, Daily News). He mentioned that several ABJ members had pushed back against him for writing the column.

The Tribune published an editorial defending itself and its coverage of the Black community. The editorial focused primarily on a column by Claude Lewis that praised the Tribune but also pointed out what he saw as its “deficiencies.”

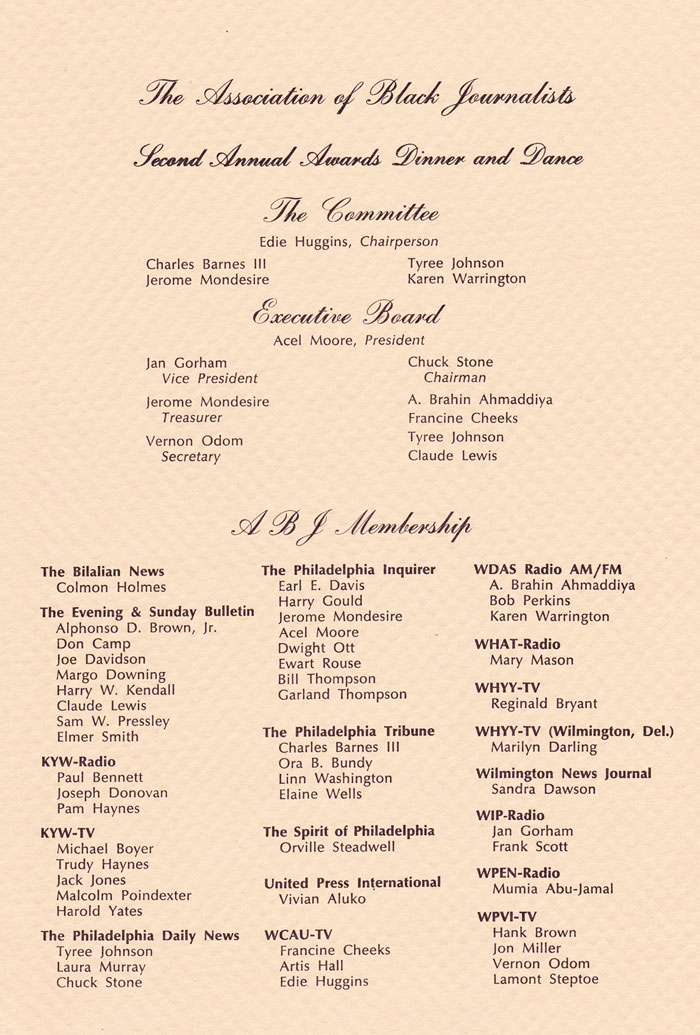

Second banquet, 1977

At ABJ’s second banquet on Feb. 26, 1977, Urban League President Vernon Jordan spoke, making what Stone called a rare weekend appearance. “’But I just didn’t think it would be wise, Jordan laughingly began, to turn down Claude Lewis (associate editor of the Bulletin), Reggie Bryant (producer of “Black Perspective on the News”) and Chuck Stone, all at the same time,’” Stone wrote in a March 15, 1977, column.

Stone noted that the speech was eloquent and that comedian Dick Gregory offered “poignant, humor commentary.” Member Michael Boyer of KYW-TV offered a film presentation titled “ABJ ’76.” Ed Bradley, CBS White House correspondent, and the Rev. Paul Washington, activist and rector at the Church of the Advocate, received awards.

Teddy Pendergrass was the entertainment for the night. He had recently left Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes, and his solo debut album would be released in June. That banquet was the one that many members still talked about (although they remember it as the first). More than 900 people attended it at the Marriott hotel on City Avenue.

“Great banquet,” recalled Johnson. “We had Teddy Pendergrass who was gonna sing for us, entertain for free. It cost us about $3,000. … He brought an entourage of people who ate and drank us out of the profits that we were gonna get.”

At one point when they were planning the banquet, Johnson said, A. Brahin Ahmaddiya and Lewis were discussing the menu. “Brahin said, ‘Well, what are you gonna do with people who don’t eat meat?’ And Claude said, ‘Sit (them) next to me.’”

Third banquet, 1978

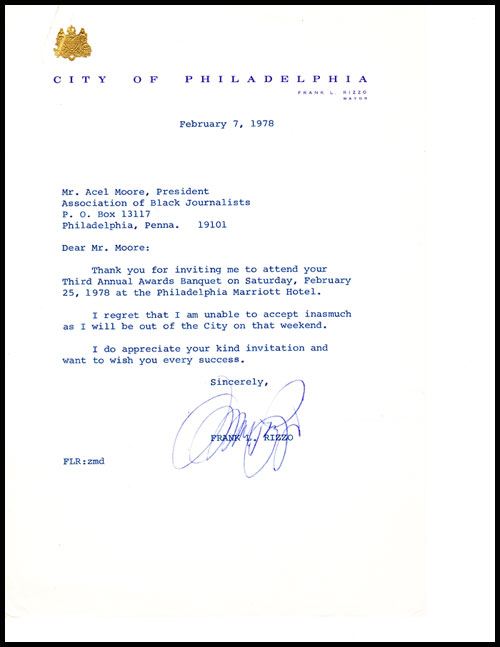

At the Feb. 25, 1978, banquet, Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson was the guest speaker. Jesse Jackson of PUSH paid a visit, as well as Washington, DC, Congressman Walter Fauntroy and actor/singer/playwright Oscar Brown Jr. Percy Qoboza, editor of South Africa’s largest Black newspaper who had been jailed for speaking out against apartheid, received the Orrin Evans-Art Peters Journalism Award. Shirley Dennis, managing director of the Delaware Valley Housing Association, was recognized for “Continuing Excellence.”

Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo, who had a fractured and antagonistic relationship with the Black community, was invited but declined, noting that he would be out of the city, according to a letter provided by Acel Moore.

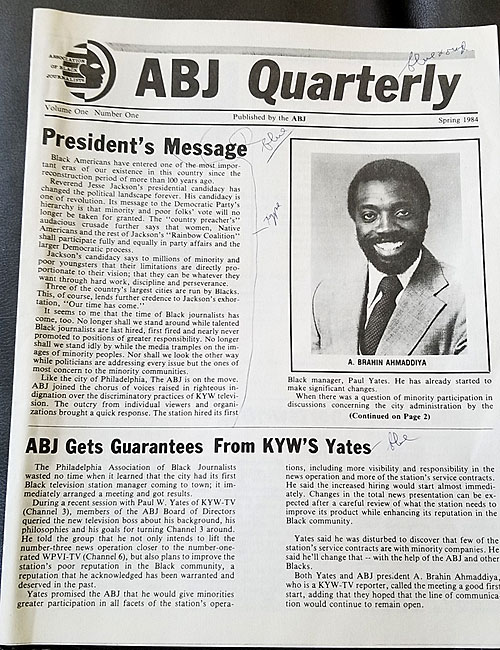

The next banquet was held in 1984 under president Ahmaddiya, and Chicago Mayor Harold Washington was the speaker, based on an invitation for the event. The dinners were apparently discontinued and then re-established in 2005 by then-president Keith Herbert, based on banquet programs from 2005 and 2006.

ABJ’s commitment to community and students

The ABJ also held community workshops on accessing the media, newsmaker lunches and forums, and workshops for students. Rizzo, who was running for re-election in 1975, declined an invitation to a mayoral forum.

The organization held its first career conference for journalists, college students and graduates, freelancers and broadcasters in 1979 during Johnson’s presidency. Local newspaper editors, and news directors from radio and TV, were invited.

ABJ and the founding of NABJ

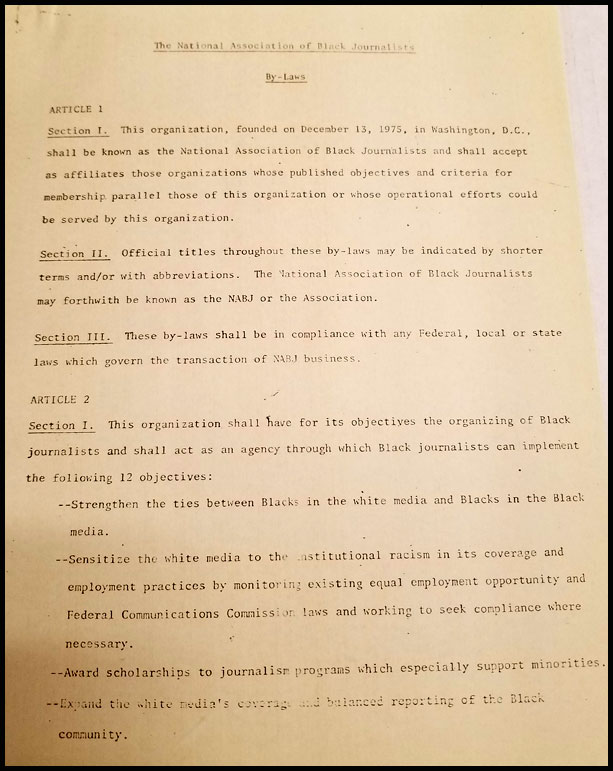

ABJ was pivotal in the founding of NABJ on Dec. 12, 1975. Several of its members were founders: Reggie Bryant, Chuck Stone, Acel Moore, Claude Lewis, Joe Davidson, Sandra Dawson (Long Weaver) and Mal Johnson. The national used parts of ABJ’s bylaws to create its own. Stone was elected president. He served a dual presidency of both the NABJ and ABJ.

In a 2017 interview, Paul Brock, NABJ’s first executive director, recalled talking with Moore, Stone and Bryant about organizing a national organization when Brock attended an ABJ dinner in Philadelphia in 1975. Brock was president of the Washington association at the time.

Journalists from both groups planned a covert meeting in the nation’s capital to coincide with a conference of Black elected officials sponsored by the Joint Center for Political Studies, according to Brock. The idea was to use the conference for elected officials from across the country to mask the meeting of Black journalists who could easily have been fired if their employers learned about it, he said. The elected officials’ meeting was set for Dec. 11-Dec. 13, 1975, in Washington. The planners sent out letters to Black journalists inviting them to cover the event; many who came didn’t know they were actually coming to discuss forming NABJ.

Stone described the NABJ as a “direct descendant” of ABJ and ABJ’s constitution and bylaws as a model for NABJ’s. Undated copies of both the Philadelphia and NABJ bylaws are among the personal papers of Acel Moore in the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University. The bylaws are almost identical except for a few areas.

“There have been times when people say Philadelphia started it,” said Brock. “No, Philadelphia did not start it. People who were in the Philadelphia and people who were in the Washington group (started it). We were not politicians. We were journalists, and we knew we had to have a constitution, so we took (part of Philadelphia’s) to save time, to save work. I wrote it on my dining room table, actually. I laid out the draft.” He credited journalist Allison Davis with helping to shape it.

The fluidity of ABJ’s name

As for the name of the organization itself, there is some inconsistency. By 1984, the names ABJ and PABJ were used interchangeably. A scholarship application for students bore the name “Association of Black Journalists” while a flyer for a series of workshops for young reporters showed it as “Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists.” In a letter, ABJ is on the letterhead and PABJ is named in the letter itself. Another letter designated it as the “Philadelphia Chapter of the Association of Black Journalists.”

The organization officially became the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists in 1985 under then-president William W. Sutton Jr. “I had a committee review our name and consider logo options,” he said. “We added Philadelphia to acknowledge that NABJ was growing and there were a number of ABJ chapters.” A new logo was created by the original designer Earl Davis.

______________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

How this history was researched

This history is based on archival documents, newspaper articles and interviews conducted independently from 2003 to 2020 primarily by Sherry L. Howard, former PABJ president and two-time treasurer, with additional interviews by Antionette Lee and others where noted throughout the website. Some of the interviewees are no longer with us.

____________________________________________________________

For a recounting of the history of the National Association of Black Journalists, read “Black Journalists: The NABJ Story,” written by Wayne Dawkins in 1997. j