FOUNDING OF BLACK COMMUNICATORS ASSOCIATED INC.

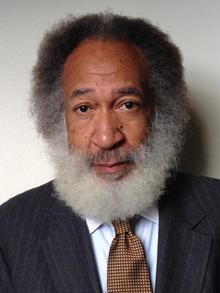

Miller Parker was a president of the Black Communicators Associated Inc., founded in 1971. He was interviewed in 2017 by Sherry L. Howard.

_____________________________________________

In 1971, an organization of Black media professionals formed the Black Communicators Associated Inc. in response to a new Federal Communications Commission (FCC) provision that TV stations “ascertain” a community’s needs by actually talking to people in the community and forbidding the stations from discriminating on the basis of race, color, religion and national origin. A violation could lead to revocation of their license.

The group registered its name with the state on June 17, 1971, and was approved on June 21, 1971. Signers were Andrew B. Reynolds Jr., Reginald Bryant, Charles D. Barnes III, Alonzo M. Saunders Jr. and Miller Parker. On Aug. 6, 1971, the group filed for incorporation with those five as signers along with Austin Culmer. It was approved on Aug. 11, 1971. The group registered its name as Black Communicators Associated Inc. but was commonly known as Black Communicators. CLICK HERE TO SEE THE DOCUMENT.

The purpose of Black Communicators was “to train, educate, stimulate interest and familiarize individuals, people and organizations in all aspects of the communications fields, such as, but not limited to radio, television, film making, newspapers, magazines and the like; to act as consultants to persons and organizations interested in the communications fields; and to own and operate radio and television stations of all kinds, newspapers, magazines and the like to carry out these purposes,” according to the filing.

Acel Moore was among the early members, said Parker, who was president of the Cap Cities/WPVI-TV Minority Advisory Board. Parker was named a producer at WCAU-TV in 1972, an appointment that was noted in Jet magazine. [1]“People.” Jet. Feb. 10, 1972. via books.google.com. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

Recollections of Miller Parker on founding of Black Communicators

“We were looking at challenging stations for not employing minorities. It was a small group of people and we said we need to step up. Black Communicators was all of the Blacks in broadcast at the time. It was newspapers, too; it was open. We had Acel Moore.

I was president of the Black Communicators (in 1971) and first president of the (Cap Cities)/WPVI-TV Minority Advisory Board. I think they were one of first TV stations in the country that had their license challenged and almost lost. That’s why they set up this group and we were part of it.

We called ourselves the Black Communicators Inc. On paper we were Black Communicators Associated Inc.

Coming out of the ‘60s, there was this move among broadcasters to put more minorities in the business because the FCC said the airwaves belonged to the people. Now, we had been in radio but never in this new thing called television. We’d been in black radio owned by white people.

Disc jockeys were almost treated like slaves. They were able to tune into their own community, which meant money: Carolina rice and Aunt Jemima pancakes and stuff like that saw the advantage of advertising and marketing within the radio station. But never on TV. There were no Black faces on television during that period.

We decided because the commission said the airwaves belonged to the people, then if that’s so, they should have some obligation to us, but not just obligation in programming to us but obligation in giving us jobs and opportunities.

So WPVI’s (which at that time was ABC) license came up for renewal, and we didn’t feel the programming formats within that station were sufficient to meet the needs of the community.

We formulated an organization and we challenged the license to make them show they were giving us equal opportunity and equal programming. The commission withheld the license for a while and told the station manager and owners you’ve got to come up with something.

So what they did is they started hiring minorities. They put on a few minority programs. Other communities heard about it and heard about us. So license challenges started spreading across the country. And that’s how we got most of our Blacks into broadcasting.

We all knew each other because there were so few of us.

We put radio, television, newspapers in the mix (of Black Communicators members). There was a mixed group of blacks. We were seeking people who could articulate our needs, whether they were PR people or advertising people.

During that period, we were not there on the professional side (of television). We learned the profession by being in the profession. If you look at it today, you look behind the cameras, we’re not there. We’ve gone backwards.

Chuck Stone, Bob Bogle (Robert Bogle of the Philadelphia Tribune) was out there as one of us; Artis Hall, cameraman; Dick Bell, Reggie Bryant.”

Forming Black Communicators

“Organization meeting: We met at the Holiday Inn. We were all notified to come and sit and talk. I think we got notification from Reggie. I think Reggie Bryant was instrumental in saying we need to do something.

Walter Palmer, (community) advocate, Mark Hyman (of Mark Hyman and Associates) were part of it. Some of the radio guys. Some were told by their bosses not to become a part of it. Sonny Hopson, radio personality (WDAS), very outspoken; Mary Mason, outspoken also. All were supportive. (The organization consisted of people his age, and younger. Ragan Henry was their attorney.)

(Ragan Henry) had a white lawyer who used to go to Washington, DC, and file all these papers and be in the court pushing against different groups and organizations and stations. It led to Ragan Henry owning radio stations across the country and TV stations. (Henry started the National Leader newspaper in the 1980s, whose editor Claude Lewis was instrumental in the founding of the Association of Black Journalists.)

He was a member of our organization but the legal arm. There were a lot of filings, once this was started and we were feared.

Black Communicators was formed around 1971. It was a small group of us, about 8 or 9. Then we tried to recruit Trudy Haynes, Edie Huggins, remember these were (the) “talent.” They were supportive and wanted to show a connection, but not necessarily a regular participant because they were fearful somebody may get pissed off and want to fire me because I’m in an advocacy group.

Who made up the organization? We were middle-management types, and we were trying to get to be the top people. So we were fighting from the bottom up. These people classified themselves as being up there.

We had bylaws, we were legal, we were incorporated.”

Request from FBI

“(Around 1973) I was approached by an arm of the FBI as president of the organization. They said we want to set up Black Communicators all over the country and we would like for you and your organization to spearhead that effort. We would not step up if you got into anything and so forth, but we would be supportive of you doing this. What do you think? I said I need to go back and talk to the board.

We met at the Bellevue. These were badge-carrying gun-carrying FBI, four or five of them in the room, two of them walking around like they weren’t paying attention and three questioning.

I think they were trying to create antagonistic groups to break up the power base of some of these radio and TV stations, (which) were very powerful. There were only four stations. I mean Walter Cronkite was king. I thought (that) what they wanted to do was break down some of the strongholds of some of these stations. They didn’t want to do it. They wanted to formulate some outside group to do it. Then they would document it, record it behind the scenes.

When I talked to the board, they said no, we don’t want to go that route. People on the board included Acel, Reggie. We all sat and chatted about it. We thought about it. And when we said no, it dissipated.

We would be at high risk going into the South, going to some places (to extend Black Communicators). I think some members of the board were fearful it would lead to a stronger advocacy, arguing and fighting. They said, no, let’s just do our thing.”

Work of WPVT Minority Advisory Board

“Once we established the WPVI Minority Advisory Board, we took it very seriously to look at their programming. They were polite, but we felt there was some animosity and resentment that we were in their business. So they were slow to make things happen.

The (Black Communicators) board was very strong toward what they wanted. We were flexing our muscles. We were able to get programming. I actually produced “Right On,” which was a Black show. We used to come on on Sunday afternoon.

Jack Jones (first African American news anchor in the region, hired in 1971) was our reporter. He volunteered to come in and do a five-minute news story. We were this “new” thing.

Matt Robinson (father of actress Holly Robinson Peete) worked at WCAU-TV. He created “Black Book,” that was his show. “Black Book” was one of those programs that got a lot of notoriety and got Matt Robinson’s name up there. Then Matt was offered an opportunity with “Sesame Street.” He created a black character on “Sesame Street” and his show name was Gordon. He was very creative.

In fact, when he left, that’s when I slid into “Right On” and the other programs.

Others on the WPVI advisory committee: Arnie Wallace, the community guy at WCAU-TV, did all the outreach. He was a member of Black Communicators. He got picked up (in 1980s) by Howard University and took over their TV station down there.

I was never involved with ABJ. I was president (of Black Communicators) about two years at the most. I was the first president.

When I got into production (at WCAU-TV), I became busier, and at that time I withdrew from president and went off into producing. And I produced for a number of years and then I went into sales. Once I got into sales, I got into a management role and went from there up to Chicago and started moving around.”

His background

“I got out of the military in ’69, got back from Vietnam, September ‘69. I recaptured my job at WCAU. I started at WCAU in the mailroom and worked my way up – 1965-66. I worked at WCAU for about two years, then I got drafted. Everybody and their mother were getting drafted.

Because of the law if (you are drafted) you’re entitled to a job when you come back. (He became an assistant director.)

I went from there to director to producer, and they said can you do some programming. That’s when I was paralleling Matt Robinson in “Black Book.” I was watching what he was doing, and I said yes I think we can get some things together. Not only did I get the Black programs, I got the white programs, too.

It just bloomed. I wasn’t looked at as the Black guy anymore. I was looked at as a producer. I was in Jet magazine, a brother becoming a producer. (Jet mentioned his promotion in its Feb. 10, 1972, edition.)[2]“People.” Jet. via books.google.com. Feb. 10, 1972. Retrieved May 20, 2022. A Philadelphia Tribune article also identified him as the vice president of the Minority Committee of Communications for WPVI.[3]“TV Producer Began as Mail Handler.” Philadelphia Tribune. via proquest.com. Jan. 25, 1972. Retrieved May 17, 2022.”

Summer student program

“Sam Evans, president of an anti-poverty organization (that grew) out of President Johnson’s Model Cities Program, wanted to get more folks into communications. So he approached me and said, I’d like for you to put together a summer program that would educate kids in communications – radio, TV, newspaper and whatever.

We put that together, a six-week program held at Benjamin Franklin High School (summer 1971). We had about 60 students. Many of them who participated in that program, once they got out, they were able to put on their resume when they went to apply for a job that they were part of this program, and were hired. A lot of them became cameramen, sound people. (These were) high school students.

We also created, and KYW is continuing to do this on-air, broadcasting by students. We started that. We were in competition with KYW. Black Communicators had this, too, but did it with ‘HAT, ‘DAS.

It was a way of exposing them to the industry. During the summer we produced television commercials, we produced newspapers, photojournalism. Anything and everything, we tried to show them the background. There’s more to it than being in front of the camera. The kids really enjoyed it.

We did it one time. Stations were committed to continuing having them come on, write news and broadcast it. They were very supportive. They were looking to us. We were going to be the feeder.

TV stations allowed us to use their facilities, tour their facilities, talk to their talent. We had 10 instructors.”

Good years

“(Black Communicators ) morphed into another organization, I think. They maintained that advisory role. Management from the stations started weeding them down and weakened them.

I heard they don’t have to have them (advisory committees) anymore. They don’t think they need them anymore. They got Black people in the newsroom, so we don’t need your advice, which is sad.

Those were great years, years when our society was really trying to do things. Johnson put that Model Cities Program together; it was incredible growth. I think it lasted about five years. They changed the climate and everything dried up.

We enjoyed that period. You could be a truck driver or you could be a construction worker or you could be someone out there fighting for justice and we kind of saw it as our mission. If we didn’t do it, who was going to do it? It was like we’ve got this opportunity, we’ve got this platform and now we’ve got the government giving us the rights. So we say, hey we got to take this shot.

The behind-the-scenes is where we’re being destroyed. There are lighting people, there are grips, there are sound, all these jobs our kids don’t see, so they don’t know how to ask. They’re not being trained. They’re not being told.”